Concrete

Optimising Heat Utilisation

Published

4 years agoon

By

admin

With Waste Heat Recovery as a viable alternative for the power needs of cement plants, Triveni Turbines presents case studies to support their findings on the role of thermal renewable fuels in aiding the cement sector inch closer to its goal of a sustainable future.

The cement industry is an energy-intensive industry. On an average, the energy cost is around 40 per cent of the cost of production for cement manufacturing. The heat generated in cement processes is generally lost up to 30 to 40 per cent.

Cement plants in India have Captive Power Plants (CPP), which are fired using fossil fuel (coal). These are in operation for several decades. Nowadays, the CPPs installed in cement plants use heat through Waste Heat Recovery (WHR) to generate power. Typically 20 to 30 per cent of the power requirement for cement plants can be fulfilled using waste heat for power generation.

Globally, WHR based plants installed in the cement industry are based on three processes, namely

- Steam Rankine Cycle System (SRC)

- Organic Rankine Cycle System (ORC)

- Kalina Based System

The function of the WHR is to recover the heat from the hot stream using Heat Recovery Steam Generators (HRSG) or Waste Heat Recovery Boiler (WHRB) to generate superheated steam. It can be used in the process (for co-generation) or to drive a steam turbine (combined cycle).

The WHR based power plants installed in cement processing plants use the heat generated through rotary kiln preheater (PH) and after quenching cooler (AQC) exhaust hot gases for power generation.

In India, the customer prefers SRC for WHR power generation in Cement Plants. Technically, in SRC, the exhaust gases from the rotary kiln pass through PH and go to the PH boiler. Similarly, mid-tapping from AQC gives hot gases to the AQC boiler. One cement kiln line requires 2 PH boilers and 1 AQC boiler. Based on the heat source, these boilers generate low-pressure steam of 12 ata to 18 ata at a temperature of 350 to 450 degree Celsius. and Low Pressure (LP)steam 2 ata to 3 ata pressure and temperature of 175 to 195 degree Celsius.

WHR-based power plants also exist in the sectors like sponge iron, steel and chemicals, which came into existence from the year 2000 onwards in the Indian market. Initially in India, the major cement manufacturers installed cement WHR plants made in China while over the last decade or so, Indian boiler and Turbine OEMs offered products indigenously designed and manufactured catering to the market dynamics, demand requirements and providing sustained long-term aftermarket services.

Cement WHR

Triveni Turbines is associated with cement WHR for many years now and has executed numerous prestigious projects with leading cement manufacturers in India and abroad. The requirement for cement WHR depends on the cement kiln capacity, heat utilisation, and plant efficiency.

Triveni is currently in the process of installing many cement WHR projects and is also working on multiple projects that are either in the enquiry or in the order finalisation stage.

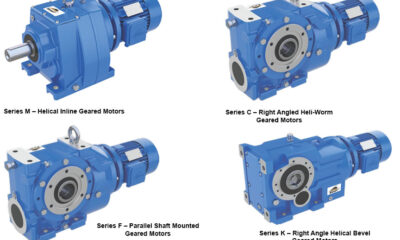

Triveni has developed efficient injection condensing turbines that use medium pressure steam as turbine inlet and low pressure as injection steam. With the addition of 7th generation turbine blades developed by Triveni, power generation output is more for input steam parameters or gas parameters.

Salient features of Triveni’s steam turbines in the cement industry are as follows:

- Integral Lube Oil tank: Triveni offers an Integral Lube Oil tank for Power House Layout and civil cost optimisations of TG House. The benefits include a reduction in the civil cost of the project.

- Mechanical Run Test (MRT): Live steam mechanical run test at Triveni’s manufacturing facility for the steam turbines. The Turbine is tested with live steam from boilers at Bengaluru works with job-mounted turbo supervisory systems, Woodward governor, and gearbox.

- In-house Manufacturing: Turbine components like blades, rotors, and casing are manufactured and assembled at Triveni’s facility.

- Vacuum Tunnel: High-speed balancing of turbine rotor on ‘Schenk’ Vacuum Tunnel

- Gear Box (Triveni Power Transmission) assembly is done along with the Turbine on the same base plate and converts into a single product. A separate foundation of the gearbox is not required.

- Inlet Valve: Triveni supplies a customised inlet governing valve is designed in-house to overcome the varied load fluctuations in the cement industry

- Injection Control Valve: Triveni supplies a specially designed globe control valve to maintain the minimum differential pressure to avoid the energy loss which results in the indirect losses in the final output.

Best practices on steam turbine design solution

Large cement companies are primarily considering WHR power plants for their Greenfield projects. Dependency on the Chinese turbines has now declined in the Indian market as the Indian OEM’s adapted to injection condensing turbines technology with a dominant leadership. Triveni has a firm reference of injection condensing turbines supplied to cement WHR plants across India.

Specific design consideration is vital in the injection and admission zone. The rotor designed by Triveni has the higher stability to offset the excitation due to fluctuating injection steam loads. To meet customer requirements for various mid-pressure and low-pressure steam combinations, an injection condensing turbine was developed by Triveni and is successfully working in the Indian Cement Industry. Design and engineering teams carried out Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) analysis and creep-fatigue analysis to address this issue. This design philosophy is a value-addition for Triveni for its robust and efficient cement

WHR solution.

Environmental concerns and the solutions offered

According to industry sources, cement manufacturing accounts for an estimated 4 to 8 per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emission, making it a significant contributor to global warming. Increasing the energy efficiency of cement plants by replacing fossil fuels with thermal renewable fuels (such as waste heat) and capturing and storing the CO2 to contain greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are some of the solutions common to the cement industry and other industrial sectors.

WHR power potential

There is a vast potential for power generation from waste heat across the world. The installation of cement WHR based power plants in China is over 80 per cent, much ahead of India. Similarly, Europe, the USA, and Latin America plan to implement WHR in their cement plants. It is observed that waste heat recovery-based power plants are emerging as an excellent value addition to the existing captive power plants. Other than reducing energy costs significantly, it can also be a reliable source of power.

Case studies of Triveni

a. Waste Heat Recovery based Power plant in Madhya Pradesh, India

Driven by Triveni 1*22.5 MWe Injection Condensing steam turbines with an inlet steam parameter of 12 Bar and 425 degree Celsius with 0.2 Bar Exhaust

Customer challenge

The steam flow in this project was from multiple sources (i.e., multiple boilers). Steam generation depends on the waste heat generated from hot gas temperature from the preheating process and AQC process. There is a variation in the steam inlet at Medium Pressure (MP) and Low Pressure (LP) side and load variation in load or power output.

Solution

The steam turbine we proposed is an Injection condensing turbine that receives MP steam as an inlet and LP steam as an injection in the middle steam path. The steam collected was from 4 No’s of Preheater (PH) boilers and 2 No’s of After Quenching Cooler (AQC) Boilers from the two cement kilns of 7,000 TPD and 8,000 TPD capacity.

The steam turbine generator (STG) is suitable for an air-cooled condenser with a new generation blade design and reaction stages. Despite various challenges, the commissioning of the Turbine was executed with quick delivery of eight months, which set a benchmark for Triveni in the cement industry.

Benefits

The company does not have a captive power plant installed, and this WHR plant has offered many benefits. The waste gas generated at around

400 degree Celsius is cooled to 130 degree Celsius, thus safeguarding the environment and simultaneously utilising the waste heat to generate almost free power.

b. Waste Heat Recovery based Power plant installed overseas

Driven by Triveni 1*30 MWe Bleed condensing steam turbines with an inlet steam pressure of

65 Bar and 505 degree Celsius with 0.1 Bar

Exhaust pressure

Customer challenge

The customer proposed installing a power plant and expanding the company’s manufacturing capacity and was on the lookout for a steam turbine solution provider. The customer wanted to generate the necessary power by banking on their captive power capacities and to ensure a steady supply for critical processes.

Solution

Triveni offered the best solution to meet the plant efficiency by utilising the waste heat recovered from the existing blast furnace for power generation.

Benefits The company entrusted Triveni’s expertise in manufacturing robust and highly reliable products. It awarded us with the supply contract of a steam turbine that benefits from improving the plant’s energy efficiency, reducing the energy cost, and transmitting surplus electricity to the grid.

To complement the above new product portfolio, Triveni’s refurbishment arm Triveni REFURB steps up to provide an aftermarket solution for the complete range of rotating equipment across the globe. From steam turbines, compressors to the gas turbine range, we have adapted ourselves to ensure that customers find a one stop solution.

Over a period of time, the existing turbines degrade thereby reducing the efficiency of the turbines by consuming more steam. The Triveni REFURB team provides solutions to enhance the efficiency of turbines of ‘Any make, Any age’ by only replacing the critical components of the turbine i.e., rotor, guide blade carriers and bearings, which ensures the efficiency is restored and thereby reducing the carbon footprint.

Triveni REFURB converts the existing turbine into injection mode turbine. The turbines are then re-engineered to allow additional steam to be injected into the turbine and improve the efficiency of the plant.

a. Conversion of Bleed Condensing Turbine to Injection Condensing

A Chinese Turbine 1*25MWe Bleed Condensing Turbine with 84 Bar 515 degree Celsius inlet conditions and 0.176 Bar Exhaust pressure

Customer challenge

A major cement Industry customer wanted to convert their existing Chinese make turbine from a 3 bleed condensing to injection condensing turbine. The pressure at the inlet was reduced to 13 Bar 425 degree Celsius as against 84 bar 515 degree Celsius. The injection parameters are 2.25 Bar 185 degree Celsius.

Solution

Due to the steep drop in inlet pressure the volumetric expansion was almost three times the original condition. We had proposed to modify the Inlet valve of the turbine and the first stage nozzles to accommodate this expansion. Two bleed ports were closed and the injection would be taken from the third bleed port. Complete re-engineering of the turbine was undertaken to adopt the upgraded steam flow path.

Benefits By keeping the existing casing and civil foundation, customers benefited by lower expenditure and improved efficiency. This would enable the customer to get a faster Return on Investment (within 2 years) and enhanced life of the turbine.

Author: Arun Mote, Executive Director, Triveni Turbine Limited

Concrete

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Executive named to succeed current managing director in 2027

Published

23 hours agoon

March 10, 2026By

admin

UltraTech Cement has appointed Jayant Dua as managing director (MD) designate who will take charge in 2027, the company announced. The appointment signals a planned leadership transition at one of the country’s largest cement manufacturers. The board has set a clear timeline for the handover and has framed the move as part of a structured succession plan.

Jayant Dua will be referred to as MD after assuming the role and will be responsible for overseeing operations, strategy and growth initiatives across the company’s network. The company said the designation follows established governance norms and aims to ensure continuity in executive leadership. The appointment is expected to allow a phased transfer of responsibilities ahead of the formal changeover.

The decision is intended to provide strategic stability as UltraTech Cement navigates domestic infrastructure demand and evolving market dynamics. Management will continue to focus on operational efficiency, capacity utilisation and cost management while aligning investments with long term objectives. The board will monitor the transition and provide further information on leadership responsibilities closer to the effective date.

Investors and market observers will have time to assess the implications of the announcement before the change is effected, and analysts will review the company’s outlook in the context of the succession. The company indicated that it will communicate any additional executive appointments or organisational changes as they are finalised. Shareholders were advised to refer to formal filings and company releases for definitive details on governance or remuneration.

The leadership change will be managed with attention to stakeholder interests and operational continuity, and the company reiterated its commitment to delivery on ongoing projects and customer obligations. Senior management will engage with employees and partners to ensure a smooth handover while maintaining focus on safety and compliance. Further updates will be provided through official investor communications in due course.

Concrete

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Rs 273 crore purchase broadens the developer’s Pune presence

Published

5 days agoon

March 6, 2026By

admin

Merlin Prime Spaces (MPS) has acquired a 13,185 sq m land parcel in Pune for Rs 273 crore, marking a notable expansion of its footprint in the city.

The transaction value converts to Rs 2,730 mn or Rs 2.73 bn.

The parcel is located in a strategic area of Pune and the firm described the acquisition as aligned with its growth objectives.

The deal follows recent activity in the region and will be watched by investors and developers.

MPS said the acquisition will support its planned development pipeline and enable delivery of commercial and residential space to meet local demand.

The company expects the site to provide flexibility in product design and phased development to respond to market conditions.

The move reflects an emphasis on land ownership in key suburban markets.

The emphasis on land acquisition reflects a strategy to secure inventory ahead of demand cycles.

The purchase follows a period of sustained investor interest in Pune real estate, driven by expanding office ecosystems and residential demand from professionals.

MPS will integrate the new holding into its existing portfolio and plans to engage with local authorities and stakeholders to progress approvals and infrastructure readiness.

No financial partners were disclosed in the announcement.

The firm indicated that timelines will depend on approvals and prevailing market conditions.

Analysts note that strategic land acquisitions at scale can help developers manage costs and timelines while preserving optionality for future projects.

MPS will now hold an enlarged land bank in the region as it pursues growth, and the acquisition underlines continued corporate appetite for measured expansion in second tier cities.

The company intends to move forward with detailed planning in the coming months.

Stakeholders will assess how the site is positioned relative to existing infrastructure and connectivity.

Concrete

Adani Cement and Naredco Partner to Promote Sustainable Construction

Collaboration to focus on skills, technology and greener practices

Published

5 days agoon

March 6, 2026By

admin

Adani Cement has entered a strategic partnership with the National Real Estate Development Council (Naredco) to support India’s construction needs with a focus on sustainability, workforce capability and modern building technologies. The collaboration brings together Adani Cement’s building materials portfolio, research and development strengths and technical expertise with Naredco’s nationwide network of more than 15,000 member organisations. The agreement aims to address evolving demand across housing, commercial and infrastructure sectors.

Under the partnership, the organisations will roll out skill development and certification programmes for masons, contractors and site supervisors, with training to emphasise contemporary construction techniques, safety practices and quality standards. The programmes are intended to improve project execution and on-site efficiency and to raise labour productivity through standardised competencies. Emphasis will be placed on practical training and certification pathways that can be scaled across regions.

The alliance will function as a platform for knowledge sharing and technology exchange, facilitating access to advanced concrete solutions, innovative construction practices and modern materials. The effort is intended to enhance structural durability, execution quality and environmental responsibility across developments while promoting adoption of low-carbon technologies and green cement alternatives. Companies expect these measures to contribute to longer term resilience of built assets.

Senior executives conveyed that the partnership reflects a shared commitment to strengthening quality and sustainability in construction and that closer engagement with developers will help integrate advanced materials and technical support throughout the project lifecycle. Leadership noted the need for responsible construction practices as urbanisation accelerates and indicated that the association should encourage wider adoption of green building norms and collaboration within the real estate and construction ecosystem.

The organisations said they will also explore integrated building solutions, including ready-mix concrete offerings, while supporting initiatives aligned with affordable and inclusive housing. The partnership will progress through engagements, conferences and joint training programmes targeting rapidly urbanising cities and growth centres where demand for efficient and environmentally responsible construction grows. Naredco, established under the aegis of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, will leverage its policy and advocacy role to support implementation.

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Adani Cement and Naredco Partner to Promote Sustainable Construction

Operational Excellence Redefined!

World Cement Association Annual Conference 2026 in Bangkok

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Adani Cement and Naredco Partner to Promote Sustainable Construction

Operational Excellence Redefined!