Concrete

Maximising AFR in Cement Manufacturing

Published

1 year agoon

By

Roshna

Shreesh A Khadilkar, Consultant and Advisor, and Former Director Quality and Product Development, ACC Ltd Thane, discusses the importance of optimising the use of alternative fuel and raw materials (TSR percentage) in cement production without affecting clinker quality.

We all know that in the calciner the CaCO3 undergoes calcination producing CaO, part of this CaO reacts with Al2O3, Fe2O3 SiO2 to form aluminates, ferrites, Belite and some CaO remain as uncombined CaO in the material that enters the kiln, this uncombined CaO further reacts, as the material passes through the kiln to form clinker of desired phase composition with at desired levels of free lime. If this uncombined CaO is less, the resultant clinker would have lower free CaO.

Due to fluctuations of moisture in the SAFR feed, the calciner outlet temperature tends to decrease/fluctuate although the calcination is complete, some of the above post calcination reactions of the CaO are decreased, as a result the uncombined CaO is higher, in the material entering the kiln. The reactions in the kiln are affected for the same throughput and either the clinker free lime is high or the clinker shows lesser C3S percentage (depending on the burnability of the kiln feed).

In plants equipped with XRD it would be possible to monitor the uncombined CaO in Hot meal and optimise the Calciner outlet temperatures so as to achieve the desired uncombined percentage of lime as explained above. If the value is much lower than the desired level it would indicate subsequent lower LSF in the clinker, so addition of lime sludge or limestone powder as explained above would maintain the desired clinker specs. These actions, if affected during the day, would help maintain the day’s average clinker quality.

Besides the variability of the moisture percentage, the ash percentage and its composition in SAFR could change the composition of calcining material and finally depending on these changes, the post calcination reactions would be affected, depending on the uncombined percentage of lime value (monitored by XRD of hot meal), the corrections as explained above would help correct the composition and maintain the burning zone performance and the resultant clinker quality. Thus, if the calciner outlet temperature / kiln inlet material / C6 material temp. (as the case may be) is maintained higher and necessary corrections are made through SAFR or through the kiln feed. We can maintain the uncombined CaO at desired level where we could get good kiln performance as well as a good/improved clinker quality even at a higher percentage of AFR/TSR.

In many plants there is a tendency to increase the clinker Fe2O3 as and when there is an excessive dust generation and dusty kiln performance, this attempt to increase Clinker Fe2O3 would not actually help in improving the kiln conditions and maintaining clinker quality. In another plant equipped with XRD, the limestone had higher Fe2O3 content and to compensate for the effect of the varying moisture of SAFR the Calciner outlet temperature was maintained at around 920oC so that the desired post calcination reactions could be achieved and the uncombined CaO (monitored by XRD of hot meal) was maintained at desired levels.

The clinker LSF also could be maintained but the Free CaO tended to be high. The hot meal XRD indicated that the belite formations were lower in hot meal as and when the clinker free lime was high. Although the Silica was contributed from the Solid AFR as this silica was sand/silt, which did not react, the clinker IR also was observed to increase by around 0.4 per cent use of pondash (having reactive silica) along with the solid AFR up to 1 per cent was observed to increase the Belite content of hot meal and the resultant clinker had desired phase formations with lower free lime. For calculation of PSF/Potential phase composition a correction was given to the clinker silica contents (by subtracting the change in IR of clinker).

Thus, it needs to be noted here that in RDF/MSW, SAFR the ash content may have coarse sand grains, which cannot at the calcination stage and it the burnability is sensitive to silica contents, such corrections of use of wet fly ash with the SAFR could be advantageous to maintain clinker quality. However, these corrections have to be affected during the day through XRD monitoring of Hot meal and subsequent Clinker (say after 40 minutes) so that at the end of the day the clinker is of desired quality specs.

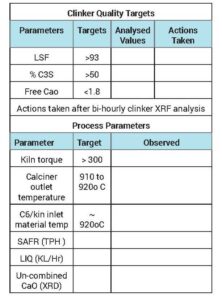

Thus, in plants coprocessing higher levels of AFR it is recommended to have a ‘bi-hourly dashboard’ and the day average clinker consistency in Quality Monitored by ‘compliance percentage to clinker specs’ as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Such a dashboard helps having the entire plant operations involved in taking bi hourly actions so as to maintain the quality and process targets with increase in SAFR/LQAFR thus, achieving a higher compliance percentage to clinker quality specs. This has enabled not only to maintain clinker quality but it also showed improvements in clinker quality.

Actions: In plant with high TSR percentage without XRD

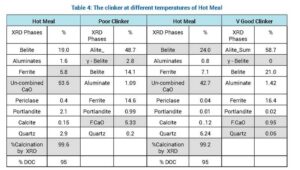

The hot meal samples at different kiln inlet material temperatures were collected at 870,900n and 930oC along with corresponding clinker samples (after say 40 minutes) and the XRD analysis was carried out at external labs. Through the bi-hourly dashboard actions the clinker compositions were maintained as per desired target. The XRD Mineralogy of Hot Meal and clinker XRD are tabulated in Table 3.

Although the plant maintains 95 per cent DOC, the XRD however indicates >99.5 per cent calcination. Thus, even in the absence of XRD using the bi-hourly dashboard optimisation of clinker quality can be made possible, however having an XRD (even a low watts XRD) would always be advantageous, especially if the kiln feed shows moderate burnability.

Other important considerations

- As discussed above bi-hourly corrections made to clinker composition could be through the SAFR/RDF mix, in one plant it could be use of waste lime sludge/ in another plant use of wet pond ash/ in another use of limestone crusher dust/ high grade limestone powder depending on the corrections desired.

- In case such materials are not available in the plant for corrections, the necessary actions bi-hourly, to adjust the clinker LSF, could be by changes in proportion of high ash coal + coal Petcoke mix in calciner or it could be even be targeting an appropriate kiln deed composition to accommodate the ash percentage of SAFR/RDF or bihourly changing the feed rate (TPH) of SAFR, as per the bi-hourly clinker composition requirements.

- Reducing conditions can have substantial effects on clinker quality like problems with sulfur integration, Alite decomposition (strength reduction), conversion from C4AF to C3A (acceleration of setting), change in color of cement (from greenish grey to brownish), the detection of reducing conditions could be done using ‘Magotteaux Test’, it is important to assess the reducing conditions whether internal or peripheral, would indicate possible reasons.

- Internal reducing conditions indicate that due to changes in liquid viscosity the larger clinker nodules are black from outside but yellow to brownish in the internal core. Such clinker nodules roll down from the transition zone with an unburnt core which disintegrates on cooling due to gamma C2S. Such nodules have high free lime, delocalised or peripheral reducing conditions due to larger size of solid AFR component (shredded size) showing CO peaks.

- The Hot meal (2Cl+SO3) needs to be reliably monitored using XRF standards of Hot Meal. Every plant would have a threshold value of (2Cl+SO3), value >3.5 is reported to cause severe depositions at kiln inlet/riser duct/cyclones.

- The kiln system should be able to handle the higher gas volumes (calciner , inlet and preheater).

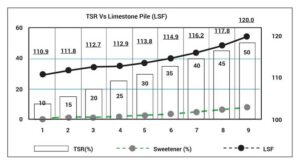

Increased percentage of AFR /TSR is associated with increase in limestone pile LSF which is linked to life of mines (Fig:2). This increase in limestone pile LSF would be more plant specific. - To lessen the impact on limestone Pile LSF/Mines life the plant would have to use, sweetener limestone (availability/cost), reduce the percentage use of high silica correctives with purer correctives, use petcoke or low ash coal (imported), use of waste lime sludges available from chemical industries.

- As discussed earlier the plant could use a mix fuel (petcoke + high ash coal), or (mix of petcoke + high ash wastes like Dolochar/spent carbon etc.) in the calciner, the mix ratio could be changed so as to improve clinker LSF during the day (as a bi-hourly actions).

High ash (high iron/high silica) wastes should not be fired through the kiln fuel; these wastes should be put through calciner fuel if feasible or along with solid wastes. It is always beneficial to have low ash coal (fuel) / petcoke in kilns. - It is recommended to use 4 per cent to 5 per cent high LSF Limestone in petcoke grinding (especially for kiln fuel). It improves the efficiency of petcoke grinding and would help to bind the sulphur during combustion in kiln, thus decreasing the SO3 of the hot meal. Using limestone decreases the SO3 fluctuations in the clinker and the excess of CaCO3 forms C3S clusters in the clinker, thus, improving clinker grindability.

- Petcoke grinding is usually controlled at 1 per cent to 2 per cent on 90 microns. However in certain grinding systems, the 45 microns residue is observed to be as high as 26 per cent to 28 per cent which could create reducing conditions and initiate some coating formation in pre pre-transition zone in kilns.

- Large storage yards to stock different types of solid AFR would help to mix the waste in certain proportions so as to achieve relative consistency in ash percentage or even chloride contents.

- An auto-sampler with shredder on the solid AFR conveyor would be useful. However, the analysis time would be around 4 to 5 hours which is too high.

- If the plant is reaching >25 per cent TSR, from a futuristics angle, having an online Cross Belt analyser like ‘Spectra Flow’ could help analyse moisture percentage, ash percentage and its constituents in real time, enabling rapid corrections to clinker compositions with necessary modifications to the kiln system even much higher TSR levels could be achievable.

- Higher TSR levels invariably are associated with increase in Hot meal alkalis, chlorides and sulphates and would necessitate chloride bypass.

- The procurement has a high responsibility of providing appropriate SAFR/RDF fuel of different ash percentage and of different chloride percentage (screened to remove sand/mud/stones).

- Wastes having CaO rich ash would always be advantageous for the same TPH of solid AFR, the TSR percentage would be higher if the NCY of the sold AFR is higher.

Conclusion

The paper indicates and discusses in some details the avenues for increased TSR percentage without affecting clinker quality. However, depending on calciner retention time and air volume availability there would be a certain maximum TSR percentage that can be achieved. It may be noted here that the kiln system would necessitate suitable upgradation for achieving a much higher TSR percentage. It is needless to mention that XRF Models with standardless software for elemental analysis of solid/liquid AFR would be advantageous and as discussed having an XRD would be a necessity to maintain clinker quality at higher TSR percentage.

Clinkers with High MgO (>4.5 per cent) would be a challenge and optimising the CaO/SiO2 ratio would be a key to improve clinker quality use of XRD in such clinkers would be an asset.

Futuristically, ‘Torrefaction Process’ (the process of degrading organic materials in a nitrogen or inert environment within a temperature range of 200oC to 300oC) of bio wastes if extended suitably to MSW wastes and other solid AFR to produce a bio coal, could become an excellent opportunity for increased TSR for cement plants.

In this paper I have tried to share some observations in a generalised manner made at different plants with different AFR/TSR percentage which could be useful for other plants for their future road map on maximising TSR percentage.

About the author:

Shreesh Khadilkar, Consultant and Advisor brings over 37 years of experience in cement manufacturing, having held leadership roles in R&D and product development at ACC Ltd. With deep expertise in innovative cement concepts, he is dedicated to sharing his knowledge and improving the performance of cement plants globally.

Concrete

NDMC Rolls Out Intensive Sanitation Drive Across Lutyens Delhi

Municipal body intensifies cleaning and monitoring across the capital

Published

16 hours agoon

March 13, 2026By

admin

The New Delhi Municipal Council has launched an intensive sanitation drive across Lutyens’ Delhi, aiming to raise cleanliness standards in the capital’s central precincts. The programme will combine enhanced manual sweeping with mechanised cleaning and systematic waste removal to cover parks, heritage precincts and prominent thoroughfares. Authorities described the initiative as a sustained effort to improve public hygiene and reduce environmental hazards while maintaining the area’s civic image.

Operational teams have been instructed to prioritise drain clearing and litter hotspots, with special attention to markets and transit nodes that attract heavy footfall. Coordination with city utilities and waste processing units will be stepped up to ensure timely collection and disposal, and supervisory rounds will monitor adherence to cleaning schedules. Officials also intend to use data-driven planning to deploy resources efficiently and to identify recurring problem areas.

The council plans to engage resident welfare associations and business stakeholders to foster community participation in maintaining cleanliness and to support behavioural change campaigns. Public communication will be amplified through notices and outreach to encourage responsible waste handling and to inform residents about collection timings and segregation norms. Enforcement measures for littering and unauthorised dumping will be reinforced as part of a broader strategy to deter violations and sustain cleanliness gains.

The move reflects a focus on urban sanitation that officials link to public health priorities and to the city administration’s commitment to maintaining civic amenities. Monitoring mechanisms will include regular reporting and inspections to review outcomes and to recalibrate operations where necessary, according to municipal sources. The council emphasised that continued community cooperation will be essential for the drive to deliver lasting improvements in the appearance and hygiene of the capital’s core areas.

Concrete

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Executive named to succeed current managing director in 2027

Published

4 days agoon

March 10, 2026By

admin

UltraTech Cement has appointed Jayant Dua as managing director (MD) designate who will take charge in 2027, the company announced. The appointment signals a planned leadership transition at one of the country’s largest cement manufacturers. The board has set a clear timeline for the handover and has framed the move as part of a structured succession plan.

Jayant Dua will be referred to as MD after assuming the role and will be responsible for overseeing operations, strategy and growth initiatives across the company’s network. The company said the designation follows established governance norms and aims to ensure continuity in executive leadership. The appointment is expected to allow a phased transfer of responsibilities ahead of the formal changeover.

The decision is intended to provide strategic stability as UltraTech Cement navigates domestic infrastructure demand and evolving market dynamics. Management will continue to focus on operational efficiency, capacity utilisation and cost management while aligning investments with long term objectives. The board will monitor the transition and provide further information on leadership responsibilities closer to the effective date.

Investors and market observers will have time to assess the implications of the announcement before the change is effected, and analysts will review the company’s outlook in the context of the succession. The company indicated that it will communicate any additional executive appointments or organisational changes as they are finalised. Shareholders were advised to refer to formal filings and company releases for definitive details on governance or remuneration.

The leadership change will be managed with attention to stakeholder interests and operational continuity, and the company reiterated its commitment to delivery on ongoing projects and customer obligations. Senior management will engage with employees and partners to ensure a smooth handover while maintaining focus on safety and compliance. Further updates will be provided through official investor communications in due course.

Concrete

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Rs 273 crore purchase broadens the developer’s Pune presence

Published

1 week agoon

March 6, 2026By

admin

Merlin Prime Spaces (MPS) has acquired a 13,185 sq m land parcel in Pune for Rs 273 crore, marking a notable expansion of its footprint in the city.

The transaction value converts to Rs 2,730 mn or Rs 2.73 bn.

The parcel is located in a strategic area of Pune and the firm described the acquisition as aligned with its growth objectives.

The deal follows recent activity in the region and will be watched by investors and developers.

MPS said the acquisition will support its planned development pipeline and enable delivery of commercial and residential space to meet local demand.

The company expects the site to provide flexibility in product design and phased development to respond to market conditions.

The move reflects an emphasis on land ownership in key suburban markets.

The emphasis on land acquisition reflects a strategy to secure inventory ahead of demand cycles.

The purchase follows a period of sustained investor interest in Pune real estate, driven by expanding office ecosystems and residential demand from professionals.

MPS will integrate the new holding into its existing portfolio and plans to engage with local authorities and stakeholders to progress approvals and infrastructure readiness.

No financial partners were disclosed in the announcement.

The firm indicated that timelines will depend on approvals and prevailing market conditions.

Analysts note that strategic land acquisitions at scale can help developers manage costs and timelines while preserving optionality for future projects.

MPS will now hold an enlarged land bank in the region as it pursues growth, and the acquisition underlines continued corporate appetite for measured expansion in second tier cities.

The company intends to move forward with detailed planning in the coming months.

Stakeholders will assess how the site is positioned relative to existing infrastructure and connectivity.

NDMC Rolls Out Intensive Sanitation Drive Across Lutyens Delhi

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Adani Cement and Naredco Partner to Promote Sustainable Construction

Operational Excellence Redefined!

NDMC Rolls Out Intensive Sanitation Drive Across Lutyens Delhi

UltraTech Appoints Jayant Dua As MD-Designate For 2027

Merlin Prime Spaces Acquires 13,185 Sq M Land Parcel In Pune

Adani Cement and Naredco Partner to Promote Sustainable Construction