Concrete

Refractories: Enabling Sustainability

Published

2 years agoon

By

admin

Refractories are the cornerstone of sustainability at a cement plant. It is important to understand their role in improving the cost efficiency of cement manufacturing and minimising its environmental impact. ICR looks into the changes in production and maintenance of refractories that have led to customised solutions, in the light of the use of alternative fuel and raw materials.

Cement manufacture is an example of human ingenuity and engineering prowess in the field of heavy industry. This essential building element, which is used everywhere nowadays, goes through a transformation process to become the finished product, and refractory is a crucial element that lies at the heart of this endeavour.

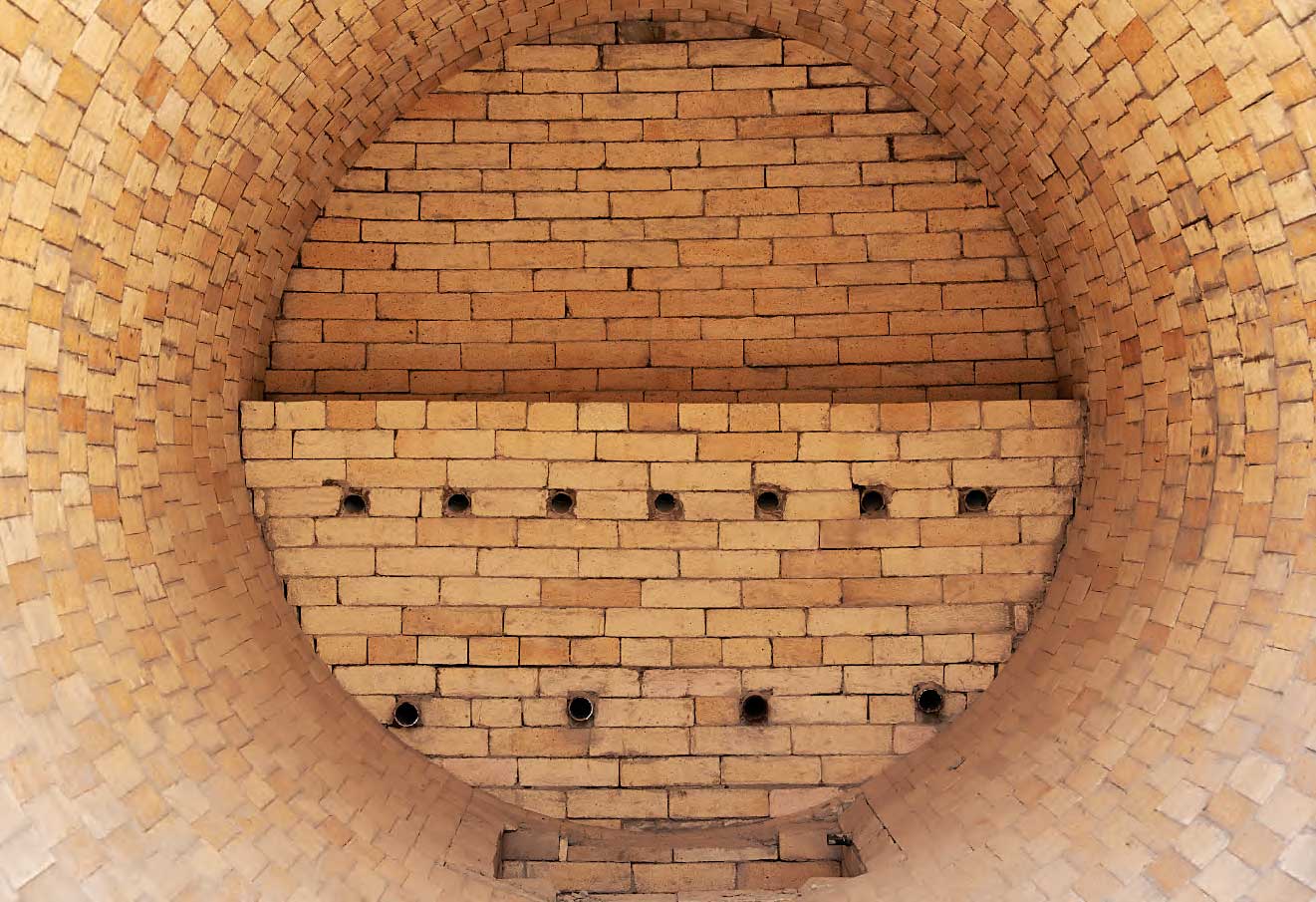

Cement plants are bustling ecosystems of industrial activity, where raw materials such as limestone, clay and shale are subjected to extreme temperatures, chemical reactions, and rigorous mechanical forces. To withstand the unforgiving environment inside cement kilns and related equipment, refractories emerge as the linchpin. These specialised materials are engineered to endure searing temperatures that could make even the hardiest of materials crumble. But refractories do more than just resist heat; they play a multifaceted role in safeguarding the integrity of the entire production process.

According to a report published in Times of India, May 2022, the Indian refractory market was sized at an estimated Rs 9,000 crore, closing in on Rs 10,000 crore in 2019. India’s steel capacity is targeted at 300 MT by 2030, as per India’s Steel Policy. Production is expected to grow to 230 MT by that time from 118 MT in FY 22. The cement industry is expected to grow by 12 per cent against a CAGR of 6 per cent historically. This means that an unprecedented need gap is waiting to be addressed by the refractory industry.

Government’s initiative of Atmanirbhar Bharat, and better understanding of the criticality of refractory to steel and cement making, has caused a change in the consumer industries’ mindset.

Companies around the world, who have built their supply chain around China, now want to de-risk China. There is now a higher demand for ‘Made in India’ products. This trend has significantly accelerated post Covid. As a result, most countries now actively seek alternative suppliers to reduce their heavy dependence on China for both raw material and finished goods.

This has created a significant opportunity for India to step in. The Indian refractory industry now must cater, not only to the increased internal demand, but also around the world.

ROLE OF AUTOMATION

Automation and technology are integral components in the effective utilisation of refractories within cement plants, especially in the context of cement manufacturing. These advanced tools play a multifaceted role in ensuring the optimal performance and longevity of refractory materials.

According to Tushar Khandhadia, General Manager – Production, Udaipur Cement Works Limited, “Technology and automation play a vital role in enhancing efficiency, accuracy, and safety in the use of refractories for cement kilns. AI and machine learning algorithms can analyse vast amounts of data to identify patterns and trends related to refractory behaviour and performance. This enables data-driven decision-making for optimising refractory selection, installation, and maintenance processes.”

One of the key functions of automation is temperature monitoring and control. Automation systems rely on advanced sensors and monitoring devices to continually measure and regulate the temperatures inside cement kilns and other high-temperature zones where refractories are employed. This precision control prevents refractory linings from experiencing overheating or cooling below the necessary levels, ultimately extending their lifespan and efficacy.

Rajesh Pathak, Managing Director, Schenck Process Solutions India, says, “Since our core value is to meet customer expectations, we meet and understand customer requirements and make alterations in the system for it to fit suitably in their process. There are two different types of MULTICOR® systems for Pyro; (a) For coal-Schenck offers combination of MULTICELL® (pre-feeder) + MULTICOR® K (Measuring Unit) and (b) For Raw Meal- Schenck offers combination of Dosing Valve (pre-feeder) + MULTICOR® S (Measuring Unit).”

Moreover, automation goes beyond mere temperature control. It incorporates predictive maintenance capabilities, coupling data analytics and predictive algorithms to foresee potential wear, damage, or deterioration in refractories. By identifying issues early on, cement plant operators can proactively schedule maintenance activities, minimising downtime and preventing production disruptions.

“By leveraging the power of automation and AI-driven analytics, the cement industry can reduce maintenance costs, enhance equipment reliability, and achieve higher energy efficiency, ultimately leading to improved productivity and profitability. We are also focusing on automation and technology up gradation to optimise the use of energy in cement plants. To achieve this, various steps have been taken towards energy conservation and technology absorption,” says Pankaj Kejriwal, Managing Director, Star Cement.

Furthermore, modern cement plants integrate remote monitoring and control systems. These centralised control rooms enable operators to oversee operations from a distance, facilitating rapid responses to issues that may affect refractory performance. This remote control aspect enhances both operational efficiency and safety.

Keyur Shah, Business Manager, SB Engineers, states, “Data from our systems gives better control to the plant and process monitoring. It allows for optimising processes. It helps with any adjustment of the fuel being pumped or to the burning zone, burner air, axil air or any other air, which is being provided to the burner. Available data also helps to make process improvements that helps optimise all critical processes at the cement plants.”

“A major challenge as of now for us occurs because the cement industry is undergoing transformation from technically automation run plants to data driven running plants. This transformation furthering the adaptability of these new changes by the plant operators or by the plant operations team is a major challenge,” he adds.

KILN ENVIRONMENT AND MAINTENANCE

Cement refractory kilns are unforgiving environments characterised by extreme conditions that can take a toll on the refractory materials used in these facilities. With temperatures exceeding 1400°C during clinker production, thermal stress and wear become significant concerns. Frequent exposure to such high temperatures necessitates regular maintenance to repair or replace damaged refractory linings, ensuring their integrity remains intact. Additionally, the chemically aggressive environment, with alkalis, sulphates and other compounds in the raw materials, can lead to erosion and corrosion. To combat this, inspections are vital to monitor conditions and the use of high-quality refractory materials resistant to chemical attack is essential.

“Our process is ISO certified. We are a premium refractory manufacturer, so we are very keen on choosing our raw material and we are doing a lot of testing of our finished goods before they are dispatched. So, you can say that there is rigorous testing of our raw material and finished goods as far as refractories are concerned,” says Mayank Kamdar, Marketing Director, Lilanand Magnesites.

Dust and particulate emissions in the cement manufacturing process can settle on refractory surfaces, potentially affecting their performance. Thus, frequent cleaning and dust removal are crucial to ensuring optimal refractory conditions and preventing blockages or reduced airflow. Thermal cycling, caused by heating and cooling cycles in the kilns, can result in thermal shock, leading to cracks and fractures in refractories. To mitigate these effects, the use of thermal cycling-resistant refractory materials and adherence to proper operating procedures are essential.

“We perform tests on refractories once in two or three years through reputed laboratories or testing agencies. However, regular inspections through shell temperature profile help us identify defects early, allowing for timely repairs or replacements to maintain the integrity and performance of the refractory lining in kilns. These intervals mentioned are indicative and may vary based on kiln operating conditions, refractory type, and specific industry guidelines,” says Khandhadia.

Abrasion is another challenge in cement kilns, caused by the constant movement of materials and interaction with gases and dust. This issue demands ongoing monitoring and maintenance, with quality refractories designed to withstand abrasion playing a pivotal role. Mechanical stress resulting from various factors, including thermal cycling and the weight of materials, poses another threat. Regular inspections and maintenance are essential to address such mechanical wear and maintain the structural integrity of refractory linings.

Lastly, the quality of refractory materials plays a pivotal role in their performance within cement kilns. Low-quality materials can lead to premature failure and increased maintenance costs. Therefore, it is imperative to use high-quality refractory materials specifically designed for cement kiln applications, and rigorous quality control in material selection and installation is necessary to maximise refractory lifespan and performance. In conclusion, maintaining refractory integrity in cement kilns involves addressing the demanding conditions they face through regular maintenance and the use of superior-quality refractory materials, ensuring the efficient and safe operation of these critical industrial facilities.

Refractories in industrial settings experience shutdowns primarily due to factors such as thermal stress, chemical attack, abrasion, mechanical impact, dust accumulation, thermal cycling, insufficient maintenance, subpar quality of refractory materials, improper installation and overheating. These shutdowns can disrupt industrial processes, leading to downtime and increased operational costs. To mitigate such issues, industries focus on regular maintenance, inspections, and repairs, employ high-quality refractory materials suited to the specific conditions, ensure proper installation techniques, and adhere to operational limits and safety protocols. These proactive measures aim to extend the lifespan of refractories,

minimise unplanned shutdowns, and maintain the reliable and efficient functioning of industrial equipment.

“Production efficiency comes from low shutdowns. If the cement plants must take a shutdown for 15-20 days every 2 to 3 months versus taking only one shutdown, the number of days of operations increases by 20 to 30 days. This means they gain one month of additional production and this is how our refractories help them achieve higher production, higher profits and achieve efficient outputs,” elaborates Vivek Singh, Sales Director – Thermal & Exports, South West Asia, Calderys Refractories India.

“Our focus is to help cement plants increase their outputs with the available infrastructure by reducing the need for shutdowns and possibilities of stopping production,” he adds.

REFRACTORIES FOR CEMENT PLANTS

In cement plants, various types of refractories are strategically employed to cater to the

distinct demands of different stages in the cement manufacturing process.

Alumina-based refractories, resistant to moderate temperatures and abrasion, are used in preheater and cyclone stages. Basic refractories, primarily magnesia-based, excel in the burning zone of rotary kilns due to their ability to withstand high temperatures and resist chemical attacks from alkalis.

Silica-based refractories find their place in cooler areas, offering good abrasion resistance and thermal insulation.

Chrome-based refractories, renowned for their resistance to extreme heat and chemical attack, are crucial in the kiln’s burning zone.

Zirconia-based refractories shine where thermal shock is a concern, such as the cooler and transition zones.

Finally, lightweight insulating refractories are deployed to reduce heat loss and improve energy efficiency, often found in areas requiring thermal insulation.

The choice of refractory type is tailored to the specific conditions of each process stage, ensuring efficiency, longevity and optimal performance in cement plants.

According to a report titled Refractories Selection for Cement Industry, August 2020 published by IN Chakraborty, Ace Calderys Limited, Nagpur, refractory selection is the most important step for the maximisation of its performance. The major deciding factors for refractory selection are the working environment where the refractory would be used. The working environment, in general, is defined by the following parameters:

• Operating temperature

• Chemical condition

• Chemical nature of solid or liquid, i.e., acidic, or basic, in contact with the refractory

• Characteristic of the gaseous environment

• Thermal shock

• Mechanical stress

• Abrasion

Refractory selection is the most important step for the maximisation of its performance. The major deciding factor for refractory selection is the working or operating environment where the refractory would be used.

Identification of critical parameters for a given working environment is vital for refractory life maximisation at optimal cost. Once the critical operating parameters are identified, the refractory should be so selected that it can withstand the operating condition for the stipulated lifespan. In the context of the refractory life in the cement rotary kiln, the lining design as well as the quality of refractory installation play a very critical role.

As a function of the cement manufacturing process, a raw meal i.e., a mix of limestone, quartz, clay and some lateritic material is fed in the kiln. This operating condition in this kiln is not severe except for in the burning zone where temperature can go up to 1450oC and the liquid content of the feed material falls in the range of 25 per cent to 27 per cent.

CONCLUSION

In the complex and high-temperature world of cement production, refractories stand as the unsung heroes, meticulously selected, and tailored to withstand the unique challenges of each stage in the manufacturing process. The choice of refractory type is a testament to the careful consideration of the specific conditions and requirements at every stage, ensuring the reliable and efficient production of this vital building material. Cement plants may be a symbol of industry, but behind the scenes, it is the adaptability and resilience of refractories that keep the fires burning and the cement flowing.

Concrete

World Cement Association Annual Conference 2026 in Bangkok

Global leaders to focus on decarbonisation and digitisation

Published

1 day agoon

March 2, 2026By

admin

The World Cement Association (WCA) will host its 2026 Annual Conference from 19–21 April 2026 at The Athenee Hotel in Bangkok, Thailand. The two-day programme will convene global cement industry leaders, policymakers, technology providers and stakeholders to examine strategic, operational and sustainability challenges shaping the sector’s next phase of transformation. The conference theme of shaping a sustainable future through digitisation, innovation and performance will frame sessions and networking opportunities across the event.\n\nThe programme will open with a comprehensive assessment of the global economic environment and its impact on cement markets, alongside regional outlooks across Asia and Europe. Speakers will address regulatory developments including carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAM) in Europe, progress in China’s carbon trading system and market dynamics in Thailand and South East Asia, and will outline practical decarbonisation pathways such as alternative fuels, next-generation supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) and calcined clay developments. Sessions will also examine AI-enabled kiln optimisation and other digital approaches to improve plant performance.\n\nDay two will focus on overcapacity challenges and industry restructuring, using case studies and regional perspectives to provide delegates with practical insights into unlocking performance while accelerating decarbonisation. Discussions will explore digital maturity and AI-driven plant operations, manufacturing optimisation, sustainable building solutions and circular concrete models, together with evolving customer requirements across the construction value chain. The event will include the WCA Awards Ceremony at the Awards Gala Dinner on 20 April to recognise excellence in sustainability, innovation, safety and leadership.\n\nPhilippe Richart, chief executive officer of the WCA, said the sector was navigating a period of profound transformation, from managing overcapacity and market volatility to deploying AI and delivering measurable decarbonisation, and that the Annual Conference would bring global leaders together to exchange practical solutions and strengthen collaboration. Registration is open and tickets include admission to the two-day event, all sessions, refreshments and lunch, exhibition access and the Awards Gala Dinner. Further information on the programme is available via the WCA Annual Conference 2026 event page and queries on sponsorship or exhibition may be directed to events@worldcementassociation.org.

Concrete

Assam Chief Minister Opens Star Cement Plant In Cachar

New plant aims to boost local industry and supply chains

Published

1 day agoon

March 2, 2026By

admin

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma inaugurated the Star Cement plant in Cachar on 28 February 2026, marking the opening of a manufacturing facility designed to serve the region. The event was attended by state officials and company representatives, and it was reported with inputs from ANI. The plant is positioned as a strategic addition to the industrial landscape of southern Assam and is expected to improve the availability of construction materials for local projects.

The establishment is expected to generate employment opportunities and to stimulate ancillary businesses in the supply chain, including transport and local vendors. State officials indicated that the plant will enhance logistical efficiency by reducing the need to transport cement over long distances, which may lower construction costs for public and private projects. Observers said the presence of a regional cement facility can support housing and infrastructure initiatives that are underway or planned.

Government representatives reiterated that the state seeks to attract responsible investment that complements regional priorities and that the administration will continue to facilitate infrastructure and connectivity to support industrial operations. The inauguration was presented as consistent with broader efforts to diversify the industrial base in the northeast and to create an enabling environment for small and medium enterprises that supply goods and services to larger manufacturers.

Company sources and the state leadership underlined the importance of maintaining environmental safeguards while pursuing industrial growth, and they signalled that compliance with applicable norms will be a priority at the new facility. The announcement was framed as a step towards balanced development that links job creation, regional supply chains and local economic resilience. The report was prepared by the TNM Bureau with inputs from ANI.

Concrete

Adani Cement, NAREDCO Form Strategic Alliance

Partnership to advance skills and sustainable construction

Published

1 day agoon

March 2, 2026By

admin

World Cement Association Annual Conference 2026 in Bangkok

Assam Chief Minister Opens Star Cement Plant In Cachar

Adani Cement, NAREDCO Form Strategic Alliance

Walplast’s GypEx Range Secures GreenPro Certification

Smart Pumping for Rock Blasting

World Cement Association Annual Conference 2026 in Bangkok

Assam Chief Minister Opens Star Cement Plant In Cachar

Adani Cement, NAREDCO Form Strategic Alliance

Walplast’s GypEx Range Secures GreenPro Certification

Smart Pumping for Rock Blasting

Trending News

-

Economy & Market4 weeks ago

Economy & Market4 weeks agoBudget 2026–27 infra thrust and CCUS outlay to lift cement sector outlook

-

Economy & Market4 weeks ago

Economy & Market4 weeks agoFORNNAX Appoints Dieter Jerschl as Sales Partner for Central Europe

-

Concrete2 weeks ago

Concrete2 weeks agoRefractory demands in our kiln have changed

-

Concrete2 weeks ago

Concrete2 weeks agoDigital supply chain visibility is critical