Economy & Market

Emerging trends & challenges in Indian cement industry

Published

14 years agoon

By

admin

Cement companies put up capacities in excess of demand in anticipation of increased consumption of cement on account of expected hike in government spending, which did not materialize. N. A. Viswanathan, Secretary General, Cement Manufacturers’ Association dwells on the issues dogging the cement industry and spells out what needs to be done by the government to tackle these issues.Cement industry, which has a direct co-relation of 1.1 to 1.2 with GDP, plays a pivotal role in the infrastructure development of the country. Buoyed with various infrastructure policies and schemes of the government, particularly after 1982 (partial decontrol) of cement, this industry had added substantial cement capacities year-after-year, much ahead of the actual cement demand taking place. However, the overall slowdown in the economy at 6.5 per cent in FY12, which further contracted to 5.3 per cent in the Apr-Jun quarter of 2012, one of the lowest in nine years, resulting in dampening construction activities, weakening of the rupee value against dollar and higher interest rates of borrowings, to quote a few, have made a severe dent on the growth of the cement industry, from an average growth of around 10 per cent in the last couple of years to a low growth of 5 per cent in FY11 and 6.3 per cent in FY12 respectively. For no fault of theirs, the cement industry has recently been criticised and also harshly penalised for under-utilising the cement capacity, without appreciating the ground realities and the factors which have contributed to reduced capacity utilisation. Today, because of the huge mismatch between demand and supply of cement, the country is having about 93 million tonnes of excess cement capacity created after making colossal investments. To revive the economy from its present slackening mode, it is now imperative for the government to enh-a-nce cement demand by taking some positive and concrete policy measures.The backgroundThough the cement industry has been in existence since 1914, appreciable growth in the cement production has been witnessed only after the introduction of partial decontrol in 1982 culminating in total decontrol in 1989 and delicensing in 1991. With the implementation of liberalisation policies of the government in 1991 followed by government’s thrust on infrastructure development in the country, the pace of the growth of the cement industry has been unprecedented.Exponential GrowthThe burgeoning growth of the industry can be gauged from the fact that for creating the first 100 million tonnes capacity, prior to partial decontrol era, the industry took 83 long years, whereas to reach the second and third 100 million tonnes mark, the period had substantially shrunk to 11 years and less than 4 years, respectively (see chart). Cement capacity which was 64.55 million tonnes in 1990-91 reached 340.44 million tonnes in 2011-12. Similarly, cement production went up from 48.90 million tonnes to 247.32 million tonnes during the same period.World Class IndustryIndia is the second largest cement producing country in the world, next only to China both in quality and technology. It produces about 7 per cent of the global production. In 2010, world production of cement was 3294 million tonnes. It is a matter of concern that even after attaining the second position, our per capita cement consumption is very low at 180 kg., which is much below the global average of 450 kg. (see table).Per capita consumption of cement is accepted as an important index of the country’s economic growth. Hence, there is enough potential to enhance our per capita cement consumption to match with the world average.With the adoption of massive modernisation and assimilation of state-of-the-art technology, Indian cement plants are today most energy-efficient and environment-friendly and are comparable to the best in the world in all respects, whether it is kiln size, technology, energy consumption or environment-friendliness. Industry has progressively reduced its energy consumption from 800-900 kwh/tonne clinker in 80s to 650-750 kwh/tonne clinker now. Similarly, power consumption registered a remarkable improvement from 105-115 kwh/tonne cement to 70-90 kwh/tonne cement during the said period. Presently, about 99 per cent of the total capacity in the industry is based on modern and environment-friendly dry process technology. Cement industry has now been making sincere efforts to utilise waste heat recovery in the plants.Problems plaguing the industryThere are a number of constraints and bottlenecks which are hindering the growth of this core sector industry. A few of the major concerns of the industry are discussed below:Excess cement capacity: Cement industry has been experiencing glut situation as there has been mammoth mismatch between cement demand and its supply. The industry had created the capacity on the back of government’s projection of potential cement demand arising out of the thrust given for infrastructure development in the country and the allocation of funds earmarked for the purpose. However, the cement demand, as projected, has not materialised, despite the capacity having been created well in advance after making huge investments.Acute shortage of coal: Coal is one of the major raw materials needed by the industry both in the manufacturing of cement and also for generating power. In the last couple of years, there has been a steep drop in the supply of linked coal to the cement industry from 70 per cent in FY04 to almost 39 per cent now, mainly due to diversion of coal to the power sector. Cement companies, therefore, have perforce to resort to either open market purchase or imported coal which works out to nearly 2 to 2.5 times higher than the domestic price or use of the alternate fuel like pet coke, lignite, etc. which also adds up significantly to the additional cost of production. What is worse, new capacities are not being given any coal under the Linkage Scheme and therefore there is a real fear that the shortage of the main fuel, with no assurance of its availability in future, may actually hamper the required capacity additions for future build up. With the increasing cost of coal and other input materials such as diesel, etc. the production cost of cement has gone up significantly.Inadequate availability of wagons: Rail is the ideal mode of transportation for cement industry. However, it has always been plagued by the short supply of wagons, particularly during the peak period. In addition to this, infrastructure constraints and also not factoring the points of view of the cement industry, which is one of its largest consumers, in the policies of the railways have been hampering the planned movement of cement to the consumption centres, adversely impacting the production schedule and also increasing the overall transportation cost of cement. Rail share for cement which was 53 per cent a couple of years back has come down to 35 per cent now, which is a matter of great concern both to the cement industry and the railways.Cement highly taxed: Although cement is a high volume low value product, it is one of the highly taxed commodities (60 per cent of the ex-factory price), even more than luxury goods. This is exclusive of the freight transportation, which is about 20 per cent of the operating cost. The levies and taxes on cement in India are far higher compared to those in the countries of Asia-Pacific region or even compared to the developing economies like Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Cement and steel are two major materials needed for construction of any infrastructure. However, it is ironic that the rate of VAT charged on cement and steel differs vastly. While the value-added tax (VAT) on steel is only four per cent, it is 12.5 per cent on cement/clinker which goes up to even 15 per cent in some of the states.Steep fall in cement exports: With the high incidence of government levies, infrastructure constraints at ports and the regulatory policies of the government providing encouragement for import of cement with nil custom duty, the export of cement and clinker from India has been steadily and continuously declining from 9 million tonnes in FY07 to 3.5 million tonnes in FY12, despite the fact that Indian cement industry is presently having the substantial excess capacity of cement and clinker.Use of fly ash unviable: Cement industry’s initiative and investment to the tune of more than Rs 1000 crore for effectively utilizing the industrial waste fly ash, which was otherwise posing a nuisance as a health hazard, has helped the thermal power plants in addressing and tackling the menace of fly ash related health and environmental hazards. However, power plants which had been earlier supplying fly ash to the cement industry free of cost have for the last couple of years, as per the order of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, started charging for fly ash from November 2009. The order has also made it mandatory for the cement plants having captive power plants to supply 20 per cent of the fly ash generated as free of cost to the small scale brick manufacturers, etc. within the vicinity of 100 kms of their plants. Both these have severely impacted the production cost of cement and also seriously threatened the fly ash recycling potential in the country.XII Plan – cement demand projectionsAs per the report submitted to the Planning Commission recently by the Working Group on Cement Industry for XIIth Plan, the country’s cement production and capacity is estimated to surge from 247.32 million tonnes and 340.44 million tonnes respectively in FY12 to 407.4 million tonnes and 479.3 million tonnes respectively by FY17.Future OutlookThe slackening economy will take at least one or two years to bounce back to its earlier level. This would, as a thumb rule, apply to the cement industry also. Since India has been emerging as one of the fastest growing economies in the world, the future outlook for cement looks to be bright, provided government formulates facilitating growth oriented policies so that our per capita cement consumption matches with at least with some of the developing economies.Measures for stimulating cement demandIt is imperative to bring back this core cement industry on higher and faster growth trajectory by revival of cement demand through faster growth of infrastructure sector, including roads, ports, airports, housing, irrigation projects, and so on. This would be possible particularly by bringing out more encouraging schemes for affordable housing with income tax relief and by constructing long-lasting cement concrete roads and adopting cement concrete canal lining to conserve 50 per cent precious water that presently seeps through our unlined canals. Water thus saved can be effectively utilized for our agriculture and other needs. The government’s long cherished ‘dream’ to provide ‘world-class standard roads’ can be fulfilled only if cement concrete roads and white topping (a technology on which a concrete layer is laid on the existing bitumen road) are adopted in the country on a larger scale. It is a well-established fact that cement concrete roads are long-lasting, maintenance-free for 30-40 years and today, in most of the cases, are even economical than bitumen roads in the construction stage itself and are, therefore, much-needed for the exponential growth of our economy. Further, cement roads can simultaneously resolve, without entailing any extra financial cost, a number of national issues and problems the government is grappling to find solutions even after spending thousands of crores of rupees every year. The problems which would be addressed are – (a) conservation of diesel and petrol up to 14 per cent as heavy load carriers consume less fuel on concrete roads than while plying on bitumen roads (b) preservation of precious foreign exchange being spent on the import of bitumen used in the construction of roads (c) utilization of fly ash up to 35 per cent, disposal of which is a nuisance and health hazard (d) conservation of 10 per cent electricity used for the street lights (e) protection of our quarries and mines and above all (f) generation of substantial downstream employment.Coal supply and wagon availability to the cement industry, which have become very acute and uncertain in the recent past, needs to be assured on a consistent and regular basis to the cement industry to facilitate it to meet the projected cement demand of the country.Further, the government needs to initiate certain measures in the form of providing tax incentive to the industry, reduce the overall tax value on the commodity and phase out cross subsidy on electricity, diesel and railway freight in a gradual manner. The government can also consider classifying cement as "Declared Goods" like steel having a uniform VAT rate of 4 per cent throughout the country. The overall taxation value on cement can be brought down to a level of 20-25 per cent of ex-works selling price from the current level.Tax incentive should also be pro-vided by the government for pro-moting blended cement in the larger interest of mineral conservation, waste utilization and bringing down carbon emission.Above all, level playing field needs to be provided to the domestic manufacturers to encourage cement and clinker exports by re-imposing custom duty on cement, which is nil at present. Additionally, Ready Mix Concrete (RMC) needs to be encouraged leading to bulk supply of cement and consequent reduction in pack-aging cost.It is a matter of record that even during the worst phase of economic slow-down, the Indian cement industry has surprised the economy watchers by its pace of sustained growth bucking the general trend of negative or slow growth of economy and the industry sector. It is, therefore, not too optimistic to presume that if the suggested measures are implemented, the cement industry will not only become a leader amongst the various sectors of the industry but will also emerge as a showpiece of model infrastructural growth contributing, in turn, to economic growth.

You may like

-

JK Cement Crosses 31 MTPA Capacity with Commissioning of Buxar Plant in Bihar

-

GST 2.0: Strengthening the Cement Sector

-

Automation, AI and Collaboration

-

Smart Motion Systems Power Cement Plants

-

Condition-based maintenance avoids over-servicing

-

Klüber Energy Efficient Synthetic High-Performance Gear Lubricating Oil

Concrete

Our strategy is to establish reliable local partnerships

Published

10 hours agoon

February 19, 2026By

admin

Jean-Jacques Bois, President, Nanolike, discusses how real-time data is reshaping cement delivery planning and fleet performance.

As cement producers look to extract efficiency gains beyond the plant gate, real-time visibility and data-driven logistics are becoming critical levers of competitiveness. In this interview with Jean-Jacques Bois, President, Nanolike, we discover how the company is helping cement brands optimise delivery planning by digitally connecting RMC silos, improving fleet utilisation and reducing overall logistics costs.

How does SiloConnect enable cement plants to optimise delivery planning and logistics in real time?

In simple terms, SiloConnect is a solution developed to help cement suppliers optimise their logistics by connecting RMC silos in real time, ensuring that the right cement is delivered at the right time and to the right location. The core objective is to provide real-time visibility of silo levels at RMC plants, allowing cement producers to better plan deliveries.

SiloConnect connects all the silos of RMC plants in real time and transmits this data remotely to the logistics teams of cement suppliers. With this information, they can decide when to dispatch trucks, how to prioritise customers, and how to optimise fleet utilisation. The biggest savings we see today are in logistics efficiency. Our customers are able to sell and ship more cement using the same fleet. This is achieved by increasing truck rotation, optimising delivery routes, and ultimately delivering the same volumes at a lower overall logistics cost.

Additionally, SiloConnect is designed as an open platform. It offers multiple connectors that allow data to be transmitted directly to third-party ERP systems. For example, it can integrate seamlessly with SAP or other major ERP platforms, enabling automatic order creation whenever replenishment is required.

How does your non-exclusive sensor design perform in the dusty, high-temperature, and harsh operating conditions typical of cement plants?

Harsh operating conditions such as high temperatures, heavy dust, extreme cold in some regions, and even heavy rainfall are all factored into the product design. These environmental challenges are considered from the very beginning of the development process.

Today, we have thousands of sensors operating reliably across a wide range of geographies, from northern Canada to Latin America, as well as in regions with heavy rainfall and extremely high temperatures, such as southern Europe. This extensive field experience demonstrates that, by design, the SiloConnect solution is highly robust and well-suited for demanding cement plant environments.

Have you initiated any pilot projects in India, and what outcomes do you expect from them?

We are at the very early stages of introducing SiloConnect in India. Recently, we installed our

first sensor at an RMC plant in collaboration with FDC Concrete, marking our initial entry into the Indian market.

In parallel, we are in discussions with a leading cement producer in India to potentially launch a pilot project within the next three months. The goal of these pilots is to demonstrate real-time visibility, logistics optimisation and measurable efficiency gains, paving the way for broader adoption across the industry.

What are your long-term plans and strategic approach for working with Indian cement manufacturers?

For India, our strategy is to establish strong and reliable local partnerships, which will allow us to scale the technology effectively. We believe that on-site service, local presence, and customer support are critical to delivering long-term value to cement producers.

Ideally, our plan is to establish an Indian entity within the next 24 months. This will enable us to serve customers more closely, provide faster support and contribute meaningfully to the digital transformation of logistics and supply chain management in the Indian cement industry.

Economy & Market

Power Build’s Core Gear Series

Published

10 hours agoon

February 19, 2026By

admin

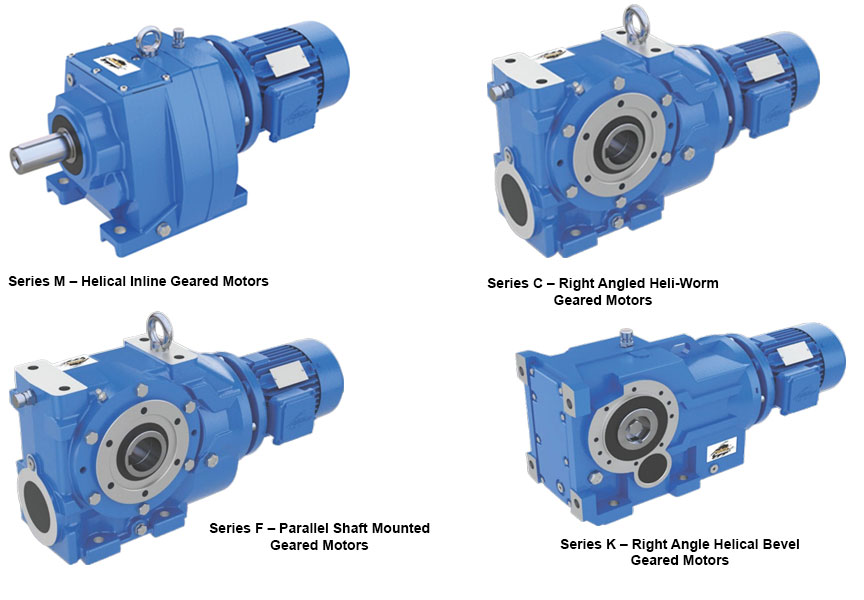

A deep dive into Core Gear Series of products M, C, F and K, by Power Build, and how they represent precision in motion.

At the heart of every high-performance industrial system lies the need for robust, reliable, and efficient power transmission. Power Build answers this need with its flagship geared motor series: M, C, F and K. Each series is meticulously engineered to serve specific operational demands while maintaining the universal promise of durability, efficiency, and performance.

Series M – Helical Inline Geared Motors

Compact and powerful, the Series M delivers exceptional drive solutions for a broad range of applications. With power handling up to 160kW and torque capacity reaching 20,000 Nm, it is the trusted solution for industries requiring quiet operation, high efficiency, and space-saving design. Series M is available with multiple mounting and motor options, making it a versatile choice for manufacturers and OEMs globally.

Series C – Right Angled Heli-Worm Geared Motors

Combining the benefits of helical and worm gearing, the Series C is designed for right-angled power transmission. With gear ratios of up to 16,000:1 and torque capacities of up to 10,000 Nm, this series is optimal for applications demanding precision in compact spaces. Industries looking for a smooth, low-noise operation with maximum torque efficiency rely on Series C for dependable performance.

Series F – Parallel Shaft Mounted Geared Motors

Built for endurance in the most demanding environments, Series F is widely adopted in steel plants, hoists, cranes and heavy-duty conveyors. Offering torque up to 10,000 Nm and high gear ratios up to 20,000:1, this product features an integral torque arm and diverse output configurations to meet industry-specific challenges head-on.

Series K – Right Angle Helical Bevel Geared Motors

For industries seeking high efficiency and torque-heavy performance, Series K is the answer. This right-angled geared motor series delivers torque up to 50,000 Nm, making it a preferred choice in core infrastructure sectors such as cement, power, mining and material handling. Its flexibility in mounting and broad motor options offer engineers the freedom in design and reliability in execution.

Together, these four series reflect Power Build’s commitment to excellence in mechanical power transmission. From compact inline designs to robust right-angle drives, each geared motor is a result of decades of engineering innovation, customer-focused design and field-tested reliability. Whether the requirement is speed control, torque multiplication or space efficiency, Radicon’s Series M, C, F and K stand as trusted powerhouses for global industries.

http://www.powerbuild.in

Call: +919727719344

Concrete

Compliance and growth go hand in h and

Published

10 hours agoon

February 19, 2026By

admin

Pankaj Kejriwal, Whole Time Director and COO, Star Cement, on driving efficiency today and designing sustainability for tomorrow.

In an era where the cement industry is under growing pressure to decarbonise while scaling capacity, Star Cement is charting a pragmatic yet forward-looking path. In this conversation, Pankaj Kejriwal, Whole Time Director and COO, Star Cement, shares how the company is leveraging waste heat recovery, alternative fuels, low-carbon products and clean energy innovations to balance operational efficiency with long-term sustainability.

How has your Lumshnong plant implemented the 24.8 MW Waste Heat Recovery System (WHRS), and what impact has it had on thermal substitution and energy costs?

Earlier, the cost of coal in the Northeast was quite reasonable, but over the past few years, global price increases have also impacted the region. We implemented the WHRS project about five years ago, and it has resulted in significant savings by reducing our overall power costs.

That is why we first installed WHRS in our older kilns, and now it has also been incorporated into our new projects. Going forward, WHRS will be essential for any cement plant. We are also working on utilising the waste gases exiting the WHRS, which are still at around 100 degrees Celsius. To harness this residual heat, we are exploring systems based on the Organic Rankine Cycle, which will allow us to extract additional power from the same process.

With the launch of Star Smart Building Solutions and AAC blocks, how are you positioning yourself in the low-carbon construction materials segment?

We are actively working on low-carbon cement products and are currently evaluating LC3 cement. The introduction of autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) blocks provided us with an effective entry into the consumer-facing segment of the industry. Since we already share a strong dealer network across products, this segment fits well into our overall strategy.

This move is clearly supporting our transition towards products with lower carbon intensity and aligns with our broader sustainability roadmap.

With a diverse product portfolio, what are the key USPs that enable you to support India’s ongoing infrastructure projects across sectors?

Cement requirements vary depending on application. There is OPC, PPC and PSC cement, and each serves different infrastructure needs. We manufacture blended cements as well, which allows us to supply products according to specific project requirements.

For instance, hydroelectric projects, including those with NHPC, have their own technical norms, which we are able to meet. From individual home builders to road infrastructure, dam projects, and regions with heavy monsoon exposure, where weather-shield cement is required, we are equipped to serve all segments. Our ability to tailor cement solutions across diverse climatic and infrastructure conditions is a key strength.

How are you managing biomass usage, circularity, and waste reduction across

your operations?

The Northeast has been fortunate in terms of biomass availability, particularly bamboo. Earlier, much of this bamboo was supplied to paper plants, but many of those facilities have since shut down. As a result, large quantities of bamboo biomass are now available, which we utilise in our thermal power plants, achieving a Thermal Substitution Rate (TSR) of nearly 60 per cent.

We have also started using bamboo as a fuel in our cement kilns, where the TSR is currently around 10 per cent to 12 per cent and is expected to increase further. From a circularity perspective, we extensively use fly ash, which allows us to reuse a major industrial waste product. Additionally, waste generated from HDPE bags is now being processed through our alternative fuel and raw material (AFR) systems. These initiatives collectively support our circular economy objectives.

As Star Cement expands, what are the key logistical and raw material challenges you face in scaling operations?

Fly ash availability in the Northeast is a constraint, as there are no major thermal power plants in the region. We currently source fly ash from Bihar and West Bengal, which adds significant logistics costs. However, supportive railway policies have helped us manage this challenge effectively.

Beyond the Northeast, we are also expanding into other regions, including the western region, to cater to northern markets. We have secured limestone mines through auctions and are now in the process of identifying and securing other critical raw material resources to support this expansion.

With increasing carbon regulations alongside capacity expansion, how do you balance compliance while sustaining growth?

Compliance and growth go hand in hand for us. On the product side, we are working on LC3 cement and other low-carbon formulations. Within our existing product portfolio, we are optimising operations by increasing the use of green fuels and improving energy efficiency to reduce our carbon footprint.

We are also optimising thermal energy consumption and reducing electrical power usage. Notably, we are the first cement company in the Northeast to deploy EV tippers at scale for limestone transportation from mines to plants. Additionally, we have installed belt conveyors for limestone transfer, which further reduces emissions. All these initiatives together help us achieve regulatory compliance while supporting expansion.

Looking ahead to 2030 and 2050, what are the key innovation and sustainability priorities for Star Cement?

Across the cement industry, carbon capture is emerging as a major focus area, and we are also planning to work actively in this space. In parallel, we see strong potential in green hydrogen and are investing in solar power plants to support this transition.

With the rapid adoption of solar energy, power costs have reduced dramatically – from 10–12 per unit to around2.5 per unit. This reduction will enable the production of green hydrogen at scale. Once available, green hydrogen can be used for electricity generation, to power EV fleets, and even as a fuel in cement kilns.

Burning green hydrogen produces only water and oxygen, eliminating carbon emissions from that part of the process. While process-related CO2 emissions from limestone calcination remain a challenge, carbon capture technologies will help address this. Ultimately, while becoming a carbon-negative industry is challenging, it is a goal we must continue to work towards.

Our strategy is to establish reliable local partnerships

Power Build’s Core Gear Series

Compliance and growth go hand in h and

Turning Downtime into Actionable Intelligence

FORNNAX Appoints Dieter Jerschl as Sales Partner for Central Europe

Our strategy is to establish reliable local partnerships

Power Build’s Core Gear Series

Compliance and growth go hand in h and

Turning Downtime into Actionable Intelligence